Story rewards people who take not necessarily the shortest path from Beginning to End, but the most compelling. The path that keeps the reader asking, “What happens next?”

I’ve found the biggest unlock has been to write the end of my story first. The end of your story has a mass to it. An element of gravity. It’s like a magnet pulling your story forward.

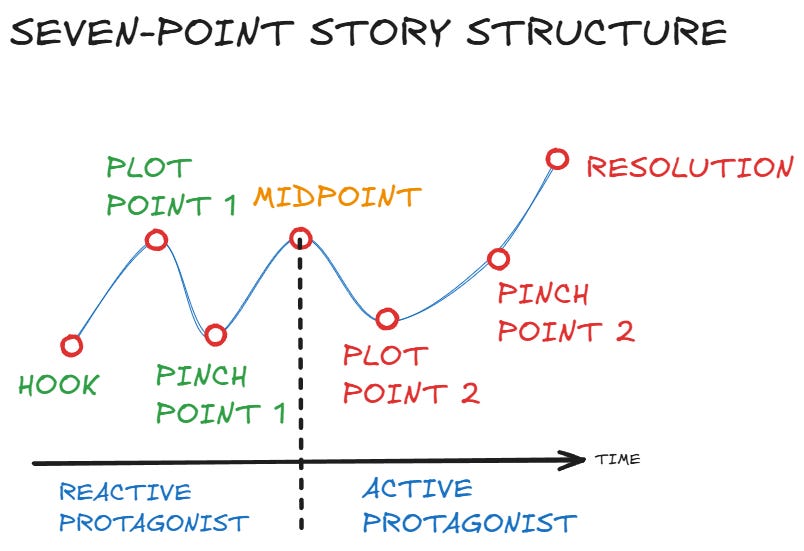

Until recently, I foolishly thought I was the only person to build stories like this. A few weeks ago, I came across a 2010 five-part lecture on story structure from author Dan Wells, which focuses on what he calls the 7-Point Story Structure. The structure itself isn’t exactly groundbreaking but how he uses it to build a story from the ground up is.

Let’s get into it.

How to use the 7-Point Story Structure to Create Your Story’s Foundation

Most story structures start with the beginning. Your “hook,” your characters, your setting, your normal world, whatever else you may need.

But that’s not how we solve problems.

Think about the best way to learn how to do something. Say you want to start a coffee shop. Where do you start? For me, I’d envision the final product then reverse engineer the steps to get there. I need to figure out where to source beans, where to rent a space, how much upfront investment I need to put down, what software to use for checkout, so on and so forth.

Yet, when telling a story, so many of us try to start at the beginning. A pilgrim on a journey with no map. We take step one, then blindly follow that path to its conclusion without a thought to whether it’s taking us to the right destination. There’s something romantic about this idea but, for me, I wander. My story wanders. Maybe you’re better at staying on track than I am. If not, give this method a try.

When using the 7-point story structure, Wells builds stories in reverse.

Step 1: Decide on your Resolution.

Your story has two resolutions — Character Resolution and Plot Resolution.

Character Resolution = Where the protagonist ends emotionally. What outlook now guides their choices? Example: Finding out Darth Vader is your father.

Plot Resolution = The actual events that close the central conflict. Example: Blowing up the Death Star.

You lock in the protagonist’s final external victory — or failure — AND their internal transformation, so every earlier beat aims at that target instead of wandering. Personally, I decide on my Character Resolution first and let that dictate how the character acts, which in turn shapes the plot. This kind of thinking also helps you create an “active” protagonist.

Step 2: Create a Hook to juxtapose with the Resolution.

Wells says, “A good rule of thumb is to start with the opposite state.”

For example, if the Resolution shows courage, the Hook might show cowardice or avoidance. Just with those two scenes nailed down, you have a strong start to both your character arcs and plot.

Think of this story structure as a narrative chiasmus: A-B-C-C-B-A. The beginning and end mirror each other while the middle serves as the story’s hinge point. The mirrored shape helps readers feel the story’s symmetry even when they can’t name it or explicitly call it out. Your opening image anchors one end of an emotional spectrum while the closing image answers or inverts it.

Here’s a great essay on Tolkien’s use of this technique with Frodo.

Step 3: Split the story in half with your Midpoint.

The story pivots from reaction → action as your protagonist decides to take control.

I missed this point while drafting my novel and couldn’t figure out why the protagonist felt so… dull. My developmental editor pointed out a simple idea: “he never makes any decisions.” He reacted to events, yes, but he never caused any events. This has led me to think of story structure first in terms of character arc, then figure out the actual events from there.

A heuristic I find helpful:

Scenes leading up to the Midpoint challenge the protagonist. Scenes that follow the Midpoint show the protagonist challenging the conflict.

Sticking to Lord of the Rings, the Midpoint of the first book comes in Rivendell. Until that point, Frodo simply does what Gandalf and Aragorn ask of him. But he’s not invited on the quest. Instead, he volunteers himself. It’s his first true moment of agency.

Step 4: Write the Plot Turn 1.

This beat links Hook to Pinch Point 1. A catalytic event forces the protagonist out of the ordinary world and toward the central conflict. They gain a goal, a new environment, or information that removes the option of retreat. It is the “point of no return.”

Think of Star Wars. Stormtroopers murder Luke’s aunt and uncle, removing every tie to the farm he’s known since childhood. Luke leaves Tatooine with Obi-Wan.

Step 5: Write the Plot Turn 2.

This beat links Midpoint to Pinch Point 2. Here the hero acquires the missing tool, truth, or resolve that makes victory possible. Often it is a revelation that reframes earlier failures. In my opinion, the most compelling of these turns focus on the protagonist’s internal state. What about themselves has kept them from succeeding? How can they overcome that? And if they do, what does that enable them to do?

If we stick to the Star Wars example, Luke finally learns to trust the Force. The key being he learns to trust, which then enables the external action of actually using the power.

Step 6: Apply pressure with the Pinch 1.

This beat links Plot Turn 1 to the Midpoint. I like to think of this moment as a time to remind your audience both of what’s at stake as well as your protagonist’s weaknesses. Nobody wants to hear a story about someone who’s constantly thriving. Make your protagonist confront something they’re scared of, something that’ll expose where they struggle.

A fun example comes from Pixar’s second best movie ever, Finding Nemo. When Marlin and Dory set off on their quest, they run into a terrifying anglerfish followed by a trio of sharks.

You may ask why I think this is so effective? Because Marlin is a coward. Ever since a barracuda ate his wife and kids — yeah, Disney is hella dark — he’s avoided the predators of the sea. The scriptwriters thus force him to come face to face with a few of the ocean’s most dangerous creatures to remind the audience how much of a coward Marlin is, thus setting him up for massive growth later in the story.

Step 7: Apply pressure with the Pinch 2.

This beat links Plot Turn 2 to the Resolution. I like to think of this moment as similar to the protagonist’s “Dark Night of the Soul.” They get pushed to the brink. They hit their lowest point, and are faced with a decision. They can either change by accepting the learning from Plot Turn 2 or stay the same. That choice leads to the Resolution, and to either victory or defeat.

For examples, think of Katniss losing Rue, Vader cutting off Luke’s arm, or Gandalf seemingly falling to the Balrog. The lower you push your characters, the higher they must climb, and the more your audience will cheer them on.

That’s the order in which Wells outlines, but here’s what the actual structure looks like once you stitch it together:

Wells uses the first three points — Resolution, Hook, Midpoint — as his ‘three-legged stool.’ A stool with two legs topples over, while one with three legs stands steady. You know how it ends, how it begins, and how the protagonist changes. From there, you test different connective tissue to see what rings truest to you, and how you can most effectively pull out the emotional notes you want to hit.

Of course, I think it’s worth sharing that there’s no specific story structure you have to use. Rather, figure out what works best for you through a process of iteration. Try the 7-point structure, then try Hero’s Journey, then ask yourself what you enjoyed and disliked from each. Combine the parts you like. Throw away what doesn’t work. Do the same for Three Act, Story Circle, and all the rest. Each structure is a tool in your toolbox. Just another lens to view the same concepts.

The end of your story drives the beginning and middle, not the other way around. Very curious what you think of this approach.

—Nathan

Interesting. Many lawyers aim to work like this in trials. They write their closing submissions and then work backwards - figuring out the evidence they need to prove along the way in order to close effectively.

This makes so much sense to me. It clarified the scaffolding what I was looking for.